Taking advantage of gas leases

SHERBURNE – There’s a good opportunity for rural landowners in Chenango County to cash in on natural gas deposits below their fields and forests, said a group of landowner advocates and experts, but only if they educate themselves on their rights and take calculated measures to protect their interests.

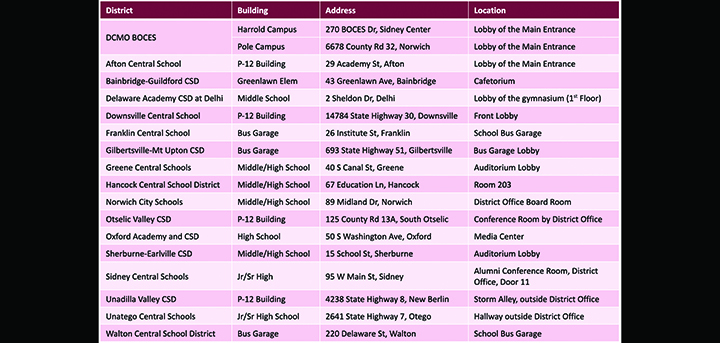

Ashur Terwilliger, a self-educated, self-proclaimed natural gas landowner’s rights advocate from Chemung County, along with attorney and natural gas legal expert Chris Denton and state agricultural resource specialist Matt Brauer offered their advice to around 100 local landowners Tuesday night at a natural gas leasing public information meeting at Sherburne-Earlville High School. The meeting was sponsored by the Chenango and Madison County Farm Bureaus.

“If it’s handled properly,” said Terwilliger, referring to gas leasing, “this could be the biggest boon to landowners and farmers in New York state in 100 years.”

The state became a hot spot in natural gas drilling and production in the late 1990s when large, deep deposits were found under what’s called the “Trenton-Black River” formations in Chemung and Steuben counties. Those same deposits extend east into Chenango County, where gas exploration is on the cusp of a similar boom, Terwilliger says, meaning a good number of landowners will be, or already have been, approached by gas companies to sign over their property rights.

Comments