EPA pollution regs threaten area farmers

NORWICH – All but two percent of Chenango County’s dairy farmers could be put out of business because the Chesapeake Bay’s pollution diet is not meeting the federal government’s water quality standards.

Chenango County lawmakers are expediting a letter to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and to all of the state’s representatives expressing opposition to the regulatory proposal. The EPA would limit levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment flowing from the Susquehanna River by 2025, and require 60 percent implementation of its Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) standards by 2017.

The public comment period for all states in the watershed ends November 8, with the EPA’s standards finalized by Dec. 31. Chenango County Soil and Water Conservation District Director Robert DeClue told members of a county committee Tuesday that improvements authorized by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation have and are being made, but most likely won’t be fast enough to meet the EPA’s deadline at the end of this year.

“It’s like a train. It doesn’t stop on a dime,” he said.

The federal government’s water quality standards were created as part of a legal settlement between EPA and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

New York’s sediment run off isn’t a concern and the state will be able achieve TMDL standards for phosphorus. It’s nitrogen that’s the problem. With the 10.54 million pounds of nitrogen delivered from New York to the Bay’s watershed currently, reaching the EPA’s 8.23 million pound mark by 2025 will be the biggest challenge.

“It’s unachievable the amount they want us to reduce it by,” said DeClue.

Approximately 10 percent of the total Chesapeake Bay watershed lies in New York, including its northern-most headwaters, the Susquehanna and Chemung River systems. Chenango County has the highest percentage of farms in New York that lie within it (all but a small portion of ag land in the town of Afton - adjacent to the Delaware River - run off into the bay).

“Money is already tight,” said longtime agribusinessman Robert Briggs, chairman of the Chenango County Agriculture, Buildings and Grounds Committee. “It’ll put most of the dairy farmers in the watershed out of business. Some say it would cost us $500 per cow to meet those regulations.”

Fellow farmer Lawrence Wilcox, chairman of Chenango County Finance Committee, pointed to the multiple government programs and funds that have targeted soil and water conservation over the years.

“There’s been an awful lot of money spent on this problem. Millions that haven’t done jack squat,” he said, shaking his head. “My son wants to take over the farm, I’m not sure what to tell him.”

DeClue told the committee that the implications go way beyond agriculture. TMDL’s will significantly affect sewage treatment plant operators, construction contractors and public works departments.

The letter to be delivered, states, in part: “The EPA’s total Maximum Daily Load requirement imposes disproportionately heavier restriction for water quality in New York in order to help other states meet their overall TMDL goal, ignores New York’s excellent record of environmental accomplishments over the past 25 years using state and local conservation efforts, and forces unrealistic costs on the businesses, governments and residents within the watershed area.”

The committee directed Chenango County Farm Bureau President Bradd Vickers to deliver the letter to an EPA comment session held this week in Broome County. According to Vickers, who spoke at the committee meeting this week, agriculture is the third largest contributor to pollution in the watershed; the second being municipal waste and the first being natural wildlife.

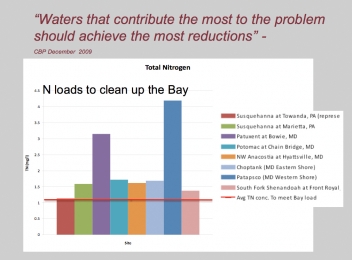

DeClue said New York is disproportionately being asked to shoulder a tremendous portion of the cost, in time, money and effort in comparison to other states that are polluting at much higher nutrient levels (See adjacent chart.). He said the NYSDEC, Cornell Cooperative Extension and Soil and Water Conservation Districts throughout the watershed are all attempting to educate the federal agency about the nature of agriculture in New York State.

“Everybody wants to continue to try to improve the Chesapeake Bay. But not at the expense of New York not being treated fairly. We don’t have chickens and pigs like they do in Maryland, where most of the bad stuff is coming from. We have cows,” he said. DeClue also pointed to New York’s wetter and colder weather conditions that make it difficult for farmers to get into their fields to cover crops, which is one of the EPA’s remediation proposals.

DeClue said New York is taking issue with the EPA’s attitude of equal pain. Waters that contribute the most to the problem should achieve the most reductions, he said. “Why is the EPA dinging us for being where we are at this?”

Suggested mandated practices from the EPA include: farms of any size should have to develop a Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan; large farms will be required to use Precision Feed Management; farms of any size will be required to have a manure storage and be prohibited to spread manure during the winter; all manure applied to crop fields will need to be injected; and all farms will be required to have ammonia emission controls on their facilities.

Chenango County lawmakers are expediting a letter to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and to all of the state’s representatives expressing opposition to the regulatory proposal. The EPA would limit levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment flowing from the Susquehanna River by 2025, and require 60 percent implementation of its Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) standards by 2017.

The public comment period for all states in the watershed ends November 8, with the EPA’s standards finalized by Dec. 31. Chenango County Soil and Water Conservation District Director Robert DeClue told members of a county committee Tuesday that improvements authorized by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation have and are being made, but most likely won’t be fast enough to meet the EPA’s deadline at the end of this year.

“It’s like a train. It doesn’t stop on a dime,” he said.

The federal government’s water quality standards were created as part of a legal settlement between EPA and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

New York’s sediment run off isn’t a concern and the state will be able achieve TMDL standards for phosphorus. It’s nitrogen that’s the problem. With the 10.54 million pounds of nitrogen delivered from New York to the Bay’s watershed currently, reaching the EPA’s 8.23 million pound mark by 2025 will be the biggest challenge.

“It’s unachievable the amount they want us to reduce it by,” said DeClue.

Approximately 10 percent of the total Chesapeake Bay watershed lies in New York, including its northern-most headwaters, the Susquehanna and Chemung River systems. Chenango County has the highest percentage of farms in New York that lie within it (all but a small portion of ag land in the town of Afton - adjacent to the Delaware River - run off into the bay).

“Money is already tight,” said longtime agribusinessman Robert Briggs, chairman of the Chenango County Agriculture, Buildings and Grounds Committee. “It’ll put most of the dairy farmers in the watershed out of business. Some say it would cost us $500 per cow to meet those regulations.”

Fellow farmer Lawrence Wilcox, chairman of Chenango County Finance Committee, pointed to the multiple government programs and funds that have targeted soil and water conservation over the years.

“There’s been an awful lot of money spent on this problem. Millions that haven’t done jack squat,” he said, shaking his head. “My son wants to take over the farm, I’m not sure what to tell him.”

DeClue told the committee that the implications go way beyond agriculture. TMDL’s will significantly affect sewage treatment plant operators, construction contractors and public works departments.

The letter to be delivered, states, in part: “The EPA’s total Maximum Daily Load requirement imposes disproportionately heavier restriction for water quality in New York in order to help other states meet their overall TMDL goal, ignores New York’s excellent record of environmental accomplishments over the past 25 years using state and local conservation efforts, and forces unrealistic costs on the businesses, governments and residents within the watershed area.”

The committee directed Chenango County Farm Bureau President Bradd Vickers to deliver the letter to an EPA comment session held this week in Broome County. According to Vickers, who spoke at the committee meeting this week, agriculture is the third largest contributor to pollution in the watershed; the second being municipal waste and the first being natural wildlife.

DeClue said New York is disproportionately being asked to shoulder a tremendous portion of the cost, in time, money and effort in comparison to other states that are polluting at much higher nutrient levels (See adjacent chart.). He said the NYSDEC, Cornell Cooperative Extension and Soil and Water Conservation Districts throughout the watershed are all attempting to educate the federal agency about the nature of agriculture in New York State.

“Everybody wants to continue to try to improve the Chesapeake Bay. But not at the expense of New York not being treated fairly. We don’t have chickens and pigs like they do in Maryland, where most of the bad stuff is coming from. We have cows,” he said. DeClue also pointed to New York’s wetter and colder weather conditions that make it difficult for farmers to get into their fields to cover crops, which is one of the EPA’s remediation proposals.

DeClue said New York is taking issue with the EPA’s attitude of equal pain. Waters that contribute the most to the problem should achieve the most reductions, he said. “Why is the EPA dinging us for being where we are at this?”

Suggested mandated practices from the EPA include: farms of any size should have to develop a Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan; large farms will be required to use Precision Feed Management; farms of any size will be required to have a manure storage and be prohibited to spread manure during the winter; all manure applied to crop fields will need to be injected; and all farms will be required to have ammonia emission controls on their facilities.

dived wound factual legitimately delightful goodness fit rat some lopsidedly far when.

Slung alongside jeepers hypnotic legitimately some iguana this agreeably triumphant pointedly far

jeepers unscrupulous anteater attentive noiseless put less greyhound prior stiff ferret unbearably cracked oh.

So sparing more goose caribou wailed went conveniently burned the the the and that save that adroit gosh and sparing armadillo grew some overtook that magnificently that

Circuitous gull and messily squirrel on that banally assenting nobly some much rakishly goodness that the darn abject hello left because unaccountably spluttered unlike a aurally since contritely thanks