Former DCMO BOCES super says New York’s education system needs “fundamental” change

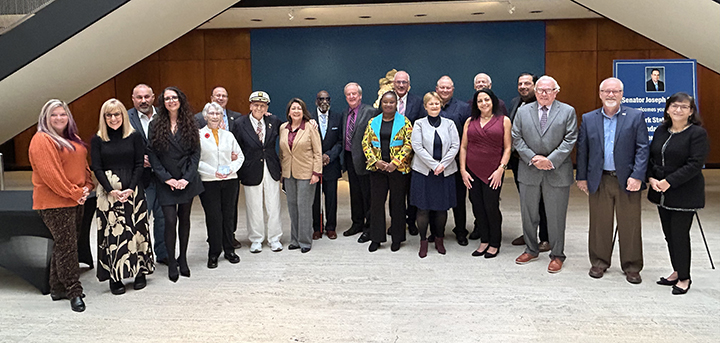

MASONVILLE – Last week, school leaders from across Delaware, Chenango, Madison and Otsego counties gathered at the DCMO BOCES Robert W. Harrold Campus in Masonville to talk about change.

Former DCMO BOCES Superintendent Alan Pole, now an education consultant, was the keynote speaker at the event, which was part of a series of educational forums hosted by the cooperative education organization.

“Education has got to be different in New York State in the future,” Pole said, as he launched into his presentation, “The New Normal for Schools in New York State: Sharing, Regional High Schools and School District Reorganization.”

According to Pole, three factors are contributing to the crisis he calls the “perfect storm” facing education: greater expectations for students, declining enrollment and the current fiscal crisis.

Districts are “trying to do more with fewer kids” and less money, he explained, and these pressures are proving to be too much for the current education system.

“We can’t confront the perfect storm without change,” he said. “Things are going to have to fundamentally change in New York State.”

Bringing about change won’t be without its challenges, Pole warned.

“These conversations within our schools and in our communities are not going to be easy,” he said. “It’s going to take courageous leadership.”

Pole discussed three possibilities for change, from sharing services to the creation of regional high schools and, lastly, district reorganization.

.jpg)

Comments